Proto-Canaanite refers to Canaan’s most ancient linear scripts, i.e., modern-day Israel and Lebanon. These scripts are essential to link a couple of short allegedly alphabetic inscriptions from Sinai and south Egypt (dated to 1900-1500 BC; see

section The Proto-Sinaitic script) and the full-blown Phoenician alphabet conventionally dated after 1050 BC. By 1330 BC. The official script in Canaan was Akkadian cuneiform, as manifested by the massive Amarna archive of official correspondence[1]. Meanwhile, Linear A thrived in Crete from 1800 to 1450 BC, preceded by substantially linear Cretan hieroglyphs (2100-1700 BC). Linear A continued as Linear B until 1200 BC (Daniels & Bright, 1996). The oldest Proto-Canaanite inscription, radiocarbon-dated to 1350 BC, was found in Tel Lachish (see section The Tel Lachish script). The Proto-Canaanite corpus consists of some 20 extant inscriptions or

fragments totaling no more than 1300 characters, 1214 of which are classified as pseudo-hieroglyphs

of the Byblos syllabary

The so-called Byblos pseudo-hieroglyphs

(later, Byblos script) constitute the core of the linear Proto-Canaanite writing

system. In the late 1920s to early 30s, the French archaeologist Maurice Dunand

discovered in Byblos, Lebanon, 16 texts of length ranging from 7 to 68

characters

Figure 1. Tablet inscriptions in Byblos pseudo-hieroglyphic script, after Dunand (1945). A. The first side of the inscription, c. B. The two sides of the inscription d.

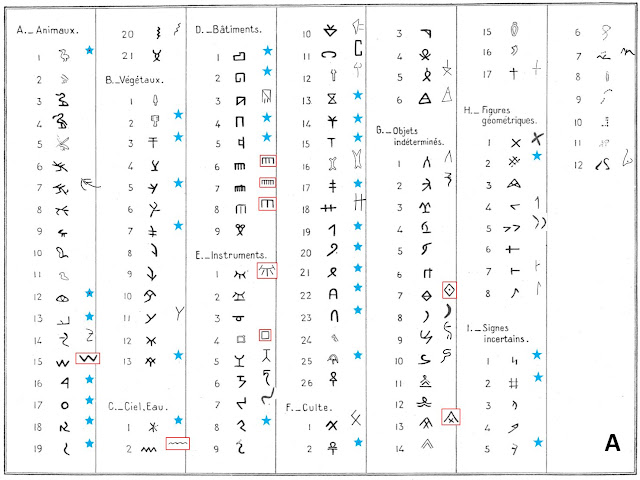

Dunand recognized 123 distinct signs (Fig. 2) in the newly discovered script. This

number was more extensive than needed for a simple syllabary. He, therefore, classified the

script as logo-syllabary, i.e., a writing system using syllabograms and

logograms, analogous to Egyptian hieroglyphic and Linear A systems. In a logo syllabary, signs are used as syllables and carry meaning. He originally dated the

inscriptions to the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, based on his intuition and the similarity of some characters with the Egyptian hieroglyphs. At the same time, he thought the oldest typical Phoenician inscription on the Akhiram sarcophagus dated to about 1300 BC. Because of the geographical

coincidence and the chronological succession, Dunand concluded that the Byblos

script was the origin of the Phoenician alphabet. However, one of the items he found was inscribed with pseudo-hieroglyphs and classical Phoenician

letters, indicating that both scripts were used in parallel for some time. Sass criticized

Dunand’s hypotheses and down-dated the artifacts to 900-830 BC and the

Phoenician alphabet to 850 BC

Figure 2. A. List of Byblos pseudo-hieroglyphics according to Dunand (1945). Corresponding Cretan (Minoan) signs and Old Balkan signs (framed in red) not identified by Dunand are juxtaposed. The blue asterisks indicate signs for which Dunand identified Cretan counterparts. B. Cretan counterparts of Byblos pseudo-hieroglyphs after Dunand (1945).

Figure 3. Standardized frequencies of common letters in Ancient Greek (AG), Modern Greek (GR), Latin (LA), English (EN), and French (FR).

This type of data and method should assist in testing hypotheses about the language behind an undeciphered script. For example, if Linear B is truly Greek, the usage frequency of its signs should significantly match the frequencies of usage of the corresponding syllables in Homeric Greek, at least. The Appendix describes a principal components analysis of the frequencies of letters, bigrams, and trigrams in lexical corpora of Ancient Greek, Modern Greek, Latin, French, English, The Iliad, The Odyssey, Theogony, and Works and Days. According to this analysis, 93.3% of the letter and cluster frequency variance is non-specific (principal component 1; PC1). The second dimension (PC2) separates the Greek lexica from the Latin-based ones, accounting for 3.6% of the variance. The third dimension (1.9%) separates Ancient and Modern Greek from the epic poetry vocabulary and the fourth (0.6%) Modern English and French from Latin. The fifth dimension (0.3%) separates English from French, and the sixth (0.2%), Modern Greek from Ancient Greek. The seventh dimension (0.06%) separates Homer (The Odyssey and The Iliad) from Hesiod (Theogony and Works and Days). The eighth dimension (0.005%) separates Theogony from Works and Days.

The Odyssey and Iliad remain inseparable. If any, their differences in letter usage represent less than 0.005% of the overall variance. The results also suggest that Modern Greek is closer to Ancient Greek than written English is to written French. Ancient Greek vocabulary is closer to Modern Green than epic poetry. Works attributed to Hesiod differ between them more from those attributed to Homer.

If the Byblos

script records a Semitic language, the frequencies of its signs should

correspond to the frequencies of the syllables of Semitic languages. The most

frequent Byblos sign would correspond to the most frequent Semitic syllable,

the second to the second, etc. Of course, attributing the so-identified

corresponding syllables to the signs of the ancient syllabary, the text must

begin making sense.

Figure 4. Frequencies of Byblos-script signs in Dunand’s (1946) first 10 published inscriptions. Data by Hans van Deukeren (2014). A. The most frequent signs. B. Signs occurring more than once but less than 15 times.

Hans van Deukeren (2014) counted the occurrences of each Byblos sign in the first ten inscriptions published

by Dunand in 1946 (Fig. 4). The frequencies

of the 32 most frequent signs drop smoothly from 63 (0.58%) to 15 (0.14%). The

frequency of the following sign drops abruptly to 11 (0.10%). There are 89 signs seen

at least twice and another 40 signs seen only once. The latter contain unclear

or broken signs, perhaps some variants of more frequent signs, special characters, and genuinely rare graphemes. We may hypothesize that

the 32 most frequent signs correspond to the most frequent Semitic phonemes or

combinations. Comparing the two Byblos tablets, both with statistically sound numbers

of characters, we notice that some letters are pretty regular in one tablet but

absent from the other. For instance, the character G7 (Fig. 2) appears seven times in the specimen shown in Fig. 1A but is missing from the model in Fig. 1B. If the two tablets record the same

language, such variation may be explained as scribe specific. Scribes appear to

choose which graphemes to use or how to write them. The script seems to have

been in perpetual experimental reform.

Dunand had noticed striking similarities

between the pseudo-hieroglyphic, on the one hand, and Egyptian hieroglyphs or

Cretan Linear A signs, on the other. His comparative table (Fig. 2B) shows one-third of the Byblos signs corresponding

to older signs from Crete. Today, this correspondence is raised to

about 50% of the Byblos script (Fig. 2A). Nine more signs are identical to Neolithic glyphs found in Balkan sites dated

millennia earlier

However, there are infinite possibilities for a sign with two or more strokes. The probability that two people will draw the same pattern without looking at each other is infinitely small. One should also contemplate the likelihood that two independent character sets will present an overlap of 50%. When drawing complex pictograms of animals, human parts, pots, or other objects, the results will be similar as far as the thing is recognized. Figurative pictograms may be considered independent inventions, and the overlap between the symbolic Byblos signs and the Egyptian hieroglyphs may be attributed to chance.

A different Proto-Canaanite script was

discovered in Khirbet Qeiyafa, a small, fortified, early Iron Age site on the

geographic frontier between Iron Age Judah and Philistia, Israel, and the

chronological transition from Israeli Iron Age I (1200–1000 BC) to Iron Age IIA

(1000–925 BC), i.e., around 1000 BC

Figure 5. Inscriptions from the same stratigraphic layer of Khirbet Qeiyafa, Israel, dated 1020-980 BC

The letters had not yet gained the

consistent stance characteristic of an alphabet. We note the presence of

typical Linear A/B signs or Old European signs, which are absent from the Byblos

pseudo-hieroglyphic script but present in latter standard Phoenician inscriptions. The sign 16 of the second line of the ʿIzbet

Ṣarṭah ostracon (𐤈; ṭēt; Theta) also appears ninth of the bottom line of the ʿIzbet

Ṣarṭah ostracon and twice in the second line of the Khirbet Qeiyafa

ostracon. It is identical to the Minoan/Mycenean sign AB77 (𐌈). It dates from the earliest period of

Vinča culture (w), 6th-5th

millennia BC

The ʿIzbet Ṣarṭah inscription was dated by letter typology to the Early Iron Age IIA, i.e., 10th century BC, with a question mark; perhaps a little earlier

Sass and colleagues

The ʿIzbet Ṣarṭah ostracon contains the attempt of an unskilled person … to write an abecedary with the twenty-two Canaanite letters.... His confusion of letters and his mistakes seem to be so serious that I would not recommend the drawing of palaeographic conclusions from any of the forms produced by him. We cannot know which letter forms are based on the contemporary scribal tradition and which are the products of either the writer’s poor training or his bad memory.

The sherd of pottery (ostracon)

was inscribed after firing, which means that the scribe may have been a

layperson – not the potter – a trainee, student, or school child learning the

alphabet. Other inscriptions from the same area and time seem to have been

written with chalk

Figure 6. The Ahiram graffito dated to 13th century BC (A) with Cretan Linear A transliteration (B) from 1800-1450 BC and the corresponding Danube-script signs from 6000-5000 BC (C). The Linear A signs are: A707 (1); A353 (2); A309a (3); AB02 (4); CHIC#40.b; AB27 (6); AB47 (7); A706 (8); A349 (9); AB302 (10); AB56 (11); and A319 (12). The Proto-Canaanite signs (A) 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 11 are identical to Danube-script (C) signs DS138, DS51, DS87, DS2, DS237, and DS65, respectively; signs 3 and 4 are commonly found in all archaic scripts (Godart & Olivier, 1996; Martirosyan, n.d.; Salgarella & Castellan, 2021; Vahanyan & Vahanyan, 2009; and Winn, 1981). Artwork by Pierre Montet and Abdnr. Marked as public domain.

Figure 7. Inscription of the Ahiram’s sarcophagus, Byblos, Lebanon, 10th century BC. Artwork by anonymous. Marked as public domain.

The

graffito of Fig. 6 is yet another example of Proto-Canaanite writing. It was found halfway

down the shaft of the tomb of Ahiram in Byblos, Lebanon, housing the homonymous sarcophagus with the oldest known typical Phoenician inscription (Fig. 7). The French archaeologist Pierre Montet (1885 – 1966) excavated the royal

tomb between 1921 and 1924, sketched the inscription, and photographed it. The text has been

interpreted to warn against looting and dates to the 13th century BC. Unfortunately, the sketch and the photograph present discrepancies

at the level of the crucial sign 7, i.e., the fourth letter of the middle line reading from the right and the second letter of the bottom line

Curiously, the anagrams ʿbd/dbʿ and bdʿ/ʿdb – with the sign ʿ rendering the Semitic ʿayin (Phoenician O) – appear on a Tel Lachish clay (see section The Tell Lachish script), the ’Išbaʿal inscription, and at least twice on the ʿIzbet

Ṣarṭah ostracon, which also features the bʿd/dʿb cluster. Yosef

Garfinkel and colleagues who dated and described the ’Išbaʿal inscription,

interpreted it as’ Išbaʿal son of Bedaʿ (read from right

to left), hence the name of the specimen

Nevertheless, Garfinkel et al. (2015) recognize

that bdʿ means producing, inventing, or beginning in Arabic. The cluster bd

alone is a contraction of byd, meaning from, or by the hand of

Figure 8. The ’Išbaʿal inscription flipped and rotated 180°.

Could the ’Išbaʿal inscription be

Greek? If we face the orifice of the jar and turn it 180°, we obtain the lower

part of Fig. 8. We may, thus, identify

the characters AΣbO)I[Σ?]IbDO. Taking character 5 as an L (as do Garfinkel et al.), this sequence transliterates as ASBOLI[S?]IBDO. A search

for Ancient Greek words containing ASBO or IBDO gave plausible

results. The word ἀσβόλη (asbolē; ASBOL-H) and the more

Attic form ἄσβολος (asbolos; ASBOL-OS)

mean soot. The verb ἀσβολόω (asboloō; ASBOL-OΩ) mans to cover

with soot. The word ἀσβολθέν is glossed by Hesychius as μέλαν (melan), black,

dark, swarthy, black marks, murky, obscure, hence Modern Greek μελάνι (melani),

ink. Brief, all the words containing the root asbol are semantically

related to soot. Ancient inks were made of soot

Among the few words containing -ibdo- we find κίβδος (kibdos; KIBDOS), meaning alloy or dross, i.e., waste, impure matter, waste product from working with metal, worthless or trivial matter, junk, rubbish. Therefore, ASBOL*IBDO* could mean ashtray, ash-bin, ash-trash, dustbin, a covered container for collecting soot, ashes, or burned waste. However, the broken grapheme 8 looks more like Σ than K. The word στιβδός (stibdos or ςibdos; StIBDOS; Hesychius στικτός, stiktos) means pricked, tattooed, spotted, dappled, i.e., marked with spots or round patches. In this case, ASBOL-SIBDO would mean marked, stained, decorated, with black, soot ink. The letter Stigma (ς) is supposedly a ligature of S and T. There is evidence that Stigma and Sigma have been confused in history and may have sometimes been represented with the same grapheme. For example, the Greek terminal S has the shape of Stigma (ς) and has probably functioned as a word endpoint (dot, stigma). Their phonetic difference may have been dialectal. Both instances of Σ in ASBOL-SIBDO may have represented Stigma pronounced /ʃ/ (as opposed to Ancient Greek San, /s/) like in English ash or Semitic’ Išbaʿal. The compound words ἀκρομόλιβδος (akro-molibdos), meaning with lead at the edge, and κυκλομόλιβδος (kyklo-molibdos), round lead-pencil, suggest that the stem ibdo may well signify a writing or drawing tool. A writing or drawing tool that works with shoot ink would be ASBOL-SIBDO.

The Greek interpretation produces two

coherent words with repeatedly attested roots. It flows freely from the form of

the intact letters without the need to distort their phonetics or add arbitrary vowels

among them. This hypothesis generates testable, in principle, predictions about

the jar’s content or decoration. It does not resort to unfalsifiable

proper names and theistic logic. It would imply that other Proto-Canaanite

inscriptions may also be Archaic Greek. All the letters of the ’Išbaʿal inscription and the other contemporary Canaanite inscriptions exist in Archaic

Greek epigraphy

The most sensible interpretation of the ’Išbaʿal inscription is obtained, however, assuming a phonetic transcription from Ancient

Egyptian with 𐰧 (O) interpreted as /w/ and sign 7 restored as 𑀏 (D) rather than 𐋉 (B). From left to right, the inscription would so read ODBISDILOBSA.

Middle Egyptian dbi means stop up, sd means clothe, and bsA means

protect. The phrase would mean something like ‘cover (plug) with a cloth to

protect’ (the content). In Late Egyptian, there is also sdi, chaudron.

According to phonocentric theory, Greek is

basically an Indo-European language installed in Helladic territories with the

arrival of the Greeks from somewhere else. Most scholars date the coming of

Proto-Greek to the transition from Early Helladic II to Early Helladic III,

around 2400−2200/2100 BC

Figure 9. Ripple in water is a surface wave. Artwork by Agustín Ruiz. Creative Commons license.

Alternatively, there have been no massive migrations. Like all cultural systems, languages do not need migration to expand but are

transited horizontally by social contact

Figure 10. Wave refraction following the Huygens–Fresnel principle. Artwork by Arne Nordmann. Creative Commons license.

Indeed, if Indo-European languages began around

the Black Sea, say in Armenia as the writing record would suggest, they would

propagate towards North, South, East, and West in a wave fashion. We should,

therefore, expect similarities between the oldest Armenian petroglyphs from

the center, and the Egyptian hieroglyphs

Figure 11. Shang dynasty Chinese inscription on an oracle bone circa 1200 BC. Artwork by anonymous. Creative Commons license.

In all linguistic phylogenetic trees I

have seen, Greek’s nearest neighbor is Armenian. Transposing this information

to a wave-like linguistic expansion model with Armenian in the center, the

first secondary Indo-European center of radiation would be Greek. Unfortunately, non-Indo-European languages are not usually included in

Indo-European analyses. In any case, Greek is a mixture of an Indo-European

language with a Pre-Greek substrate, the origin of which is debated. Beekes

An implicit explanation is that local

Pre-Greeks were familiar with all those things and had words for them. The Indo-European

Greeks arriving in waves from the Russian steppes had not seen vines, olives,

or the sea before. They were not aware of local Helladic heroes, gods, islands, and

places. They were, therefore, not expected to have had words for them and had

to borrow the local terms. However, not everything can be explained this way. Elementary

history books tell us that iron was used only after 1000 BC. Why would

Pre-Greeks have a word for iron before the arrival of the Greeks 1500 if not

3500 years earlier? Do we have words for things that will be discovered or

invented by non-English speakers in 1500 years from now? Would an American

scientist look up in long extinct indigenous American vocabularies to find a

name for a material, tool, or method, she just developed? For such terms,

Pre-Greek must be understood as contemporary to Greek but foreign. If Pre-Greek,

iron was discovered and named outside the Hellenic world. Greek borrowed the

term in historical times.

Beekes observes that certain consonant

clusters, /bd/ and /sb/ among them, do not exist or are very rare in

Indo-European languages but common in Pre-Greek. He does not specify where they

come from. Plausible origins are Ancient Egyptian and the Semitic languages of

the Levant. The cluster bd appears several times in the few

Proto-Canaanite inscriptions presented above. From the so-called’ Išbaʿal

inscription, I deduce that ASBOL means ash or soot and [S]IBDO means decorated,

covered, coated. In Middle

Egyptian (Dickson, 2006), we find the

words <Asb> (/ɑ(ː)sb/)

meaning glowing (of radiance), <Asbyw>

(/ɑ(ː)sbiːuː/), flame, <psi> (/psi(ː)/), to cook and

<wbd> (/w|uːbd/), to burn, heat, be scalded. In Late

Egyptian

In Greek, the double phonemes /ps/, /bs/,

/vs/, and /fs/ are represented by the grapheme Ψ. These are found in Ancient Greek ἕψω (‘epsō or hepsō), to boil, cook, digest, smelt, ἑψητός (‘epsētos

or hepsētos; /epsi(:)tos/), boiled, boiled fish, or Modern

Greek ψητός (psētos;

/psi(:)tos/), roast, baked. The ending morpheme -εψω (-epsō) forms the future tense of hundreds of Greek verbs

ending in -ευω (-eyō; /evo/), which reminds the also

very common Egyptian ending -yw[1]. The inversion bs/sp, or ps/sp, holds in Greek for lighting up and lighting down/out. The notion of quenching is in Greek ἑσπέρα (‘espera

or hespera) and its derivatives meaning evening, nightfall, night,

hence, west. Whereas eps

is a future morpheme, the inverse esp forms aorists. Compare, for example, the Homeric future ἕψομαι (‘epsomai or hepsomai)

with second aorist ἑσπόμην (‘espomēn or hespomēn)

from ἕπω (‘epō or hepō), to follow, accompany, escort,

attend, pursue, follow up, especially in mind, understand, succeed, etc. Yet

another example of antonymy by the ps/sp inversion involves the Ancient Greek ἁψίς (‘apsis,

hapsis), loop, mesh, net, felloe of a wheel, the wheel itself, dowel-pin,

arch or vault, triumphal arch, orbit, and ἀσπίς (aspis),

shield. Whereas hapsis implies passing through it, aspis

forbids it; it repels objects falling on it.

If ASBOL was Egyptian and ASB meant flame

(fire), we should look for possible Egyptian meanings of OL, probably transliterated

as <wl>. I found the Late Egyptian word <wl> meaning

condition

The PIE root *bhel- (2) refers to various round objects and to the notion of

tumescent masculinity. Its reconstruction was based on a collection of

morphologically, phonetically and semantically disparate words including English

balloon, ballot, bawd,

bold, boll, bollocks,

bollix, boulder, boulevard,

bull (bovine male animal), bullock, bulwark,

follicle, folly, fool, foosball,

full (to tread or beat cloth to cleanse or thicken it), pall-mall,

phallus, Greek phyllon (leaf), phallos

(swollen penis), Latin flos (flower), florere

(to blossom, flourish), folium (leaf), Old Prussian

balsinis (cushion), Old Norse belgr (bag,

bellows), Old Irish bolgaim (I swell), blath

(blossom, flower), bolach (pimple), bolg

(bag), Breton bolc’h (flax pod), Serbian buljiti

(to stare, be bug-eyed), and Serbo-Croatian blazina (pillow). The semantic relation of a clay container (bowl) with the bull, the

flower, the phallus, the pillow, and the bellows

may be questioned. The proponents do not explain how the specifications of *bhel-

into blow and bowl came about. Why and how does the metathesis

of L produce such profound semantic change? The more words we consider for the

reconstruction of a root and try to explain, the more complex, vague, and

dubious the phonocentric etymologies become. Instead, the above ‘out of Egypt’

hypothesis is based on archaeological evidence, historical considerations, and

only evident assumptions about the phonetic evolution of the Egyptian <w>. The

following graphocentric hypothesis would explain the semantic effects of the

metathesis of L from BOWL to BLOW and suggest that this metathesis could have easily

been elaborated in Europe using Archaic Greek (or “Phoenician”) graphemes.

Figure 12. Archaic Greek versions of Gamma, Lambda, and Ypsilon from Salgarella and Castellan (2021)

Fig. 12 compiles the graphemes representing the letters

Gamma, Lambda, and Ypsilon as attested in Archaic Greek epigraphy. It shows

that these letters had forms of angular or curved brackets and could be used as

arrows to indicate direction. A curved, parenthesis-like form of L is used in the ’Išbaʿal inscription (grapheme 5), while Y was curved as U in Latin

and as u in lowercase Greek. Curved forms are easier to

produce in cursive writing, whereas angular forms are easier to carve. We also note,

from Fig. 12, that these three letters

could be confused. Modern γ could be read as Y; Y1 and Y2 could be read as L7; L1

is identical to G2, L2 to G5, G6 to L8, and so on.

Given the dialectical and diachronic

similarities in pronunciation between Ancient Greek O, Y, OY, Ω (compare, for

example, Attic βουλή, boulē with Doric βωλά, bōla, both meaning counsel,

design, deliberation, decree), Latin U (frequently replacing the Greek O), and

Celtic or English OU, OO, and the digram OW, it is conceivable that the latter

is a phonetic transcription of an ancient Ω. Whereas OW does

not make much graphic sense in English today, Ω does. It

represents an Ω-shaped object, either convex (blown, Ω) or concave (bowl, ℧). The

archaic cluster BΩ< would represent an Ω-object brought

close to a B-like object, the lips. The direction of movement would be

indicated by the arrow <, read as L. A bowl (BΩ<) is a drinking

tool. The digraph Ω< stands for ℧, and BΩ<, for B℧. When < is on the right side of Ω, it signifies a

diminution of the Ω-object, e.g., pouring from a bowl into a mouth. When

< moves to the left side of Ω, it represents a magnification of the Ω-object. Between

the lips (B) and the Ω-object, the grapheme < nicely describes the air

blown from the lips (B) and causing the Ω-object to augment (<Ω = Ω).

In English, the cluster B<Ω reads blow, i.e., lips (B) + air stream (<)

+ inflated convex object (Ω). When articulated, B shows the lips while L shows

the mouth cavity using the tip of the tongue. BLΩ shows the direction from the mouth cavity (BL) to the Ω-object, whereas BΩL indicates a

direction from the lips (orifice) of the Ω-object to the mouth cavity (L). Whether considering

their graphemes or their phonetic transcription, blow and bowl are

iconic words and good examples of the iconicity of linguistic signs. The metathesis of L is not erroneous but

semantically significant.

As the above hypothesis predicts, BLΩ is used for rising, expanding, or voluminous objects

such as βλωρός (blōros), fig leaf, βλώσκει (blōskei),

rising, and βλωθρός (blōthros), tall, well developed, also glossed as εὐαυξής (eyayxēs;

Hesychius), akin to αὔξη (ayxē),

dimension, and αὔξησις (ayxēsis),

growth, increase, multiplication, increment, amplification, augment; compare English

blather, bladder, blah, Scottish blether, Old Norse

blaðra, German bladdern, French blabla, all thought to

derive from Proto-Germanic *blodram, meaning to speak inarticulately,

talk nonsense. In addition, βλωμός (blōmos) is glossed as ψωμός (psōmos) and translated as morsel, bit, always referring to

bread or to man’s muscles. Bread and a man’s muscles have the common characteristic

of raising, and growing in volume, but a man’s muscles are never morcellated. The

morsel interpretations are due to semantic drift. Bread is usually morcellated,

but it is risen (blōmos) and cooked in the first place (psōmos; see Late Egyptian <bsw> and <ps>

above). The original meanings of blōmos, psōmos,

and Modern Greek psōmi (ψωμί; bread) were more likely raised, inflated,

and baked. Instead, BΩL signifies small

volumes of materials or diminished objects, e.g., βωλάζω (bōlazō), to clod,

or βῶλος (bōlos), a clod of

earth, lump, as of gold, nugget, hence, βώλινος (bōlinos), made of

clay.

The stems bōl and blō may be confused by erroneous phonetic

metathesis of consonants or vowels, as it is generally assumed, but semantic

drift mechanisms should not be neglected. The French term boulanger,

meaning baker, bread maker, seems phonetically closer to bōl (bowl)

than to blō (blow;

raised, and baked bread). How come a word about bread (Greek blōmos) starts with boul- and not with blou-? And

how come the French word for bread-maker has nothing to do with the French word

for full-blown and baked bread, pain? What does boulanger really

mean?

The Modern French spelling, boulanger, first appears

in a 1299 AD text. The Medieval Latin form with the same meaning, bolengarius,

is first attested in 1100; it becomes bolengerius circa 1120,

and bolengier circa 1170. It has been deduced that the

first part of the word derives from the hypothetical Germanic root *bolla,

as does the Dutch presumed cognate bolle, and High German bolla,

all meaning round bread. According to the Germanic-origin hypothesis, the

ending -anger would have derived from the hypothetical Old Frankish *-enc

ending, from Germanic -ing, as in Old Picard boulenc (bun

or bread maker), normalized with the French ending -ier. Thus, Old

French bolengier and boulanger (baker) would have derived from

Old Picard boulenc (bun-maker, bread-maker), from Low Frankish *bollā

(bun) + -enc (-ing), from Frankish *-ing (-ing), from

Proto-Germanic *-ingaz (-ing)[2]. This hypothesis builds

upon a series of also hypothetical foundations, rests on hypothetical

languages, and ignores the attested term bolengarius. The

following proposition of Greek and Latin origin is much more parsimonious.

There is little doubt that the boul-

of boulanger and the bole- of bolengarius

are cognates of Middle French boule, meaning ball, globe, bowl, scoop, bauble,

spherical object, and Old French bole, knob (edema, swell, lump,

tumefaction, bump), club (stick with a thick end), mace (mass, bulk;

note the antonymy of English bulk/club created by the inversion bulk/klub,

*klub giving English club). In Latin, we have bulla, for any

object swelling up (hence, for bread), and thus becoming round like a bubble, water-bubble,

or for objects that are rounded by art, studs, amulets, metaphorically, trifle,

vanity etc., and its cognates bullo, bullŭla, bulbus (or bulbŏs;

Greek βολβός, bolbos), bulga, a leathern

knapsack, bag, the womb, etc. Note the hollowness of bul-objects indicated by the grapheme U.

In English, we have bulb, bubble,

boil, and bulimia, from Latin būlīmo, from Greek βουλιμιῶ, boulimiō, to suffer from βουλιμία (boulimia), bulimia or

insatiable, ravenous hunger, fill (O) and empty (U) the stomach.

Instead, Latin bu-l

becomes bol- for massive spherical or semispherical objects such as bōlētus (Greek βωλίτης; bōlitēs), a mushroom, bōloe (Greek βῶλοι; bōloi; clods of earth), precious

stones, bolbĭtŏn (Greek βόλβιτον; bolbiton), the dung of cattle. Therefore, the bol of bolengarius is neither hollow

nor swollen but a massive spherical object. The letter U was added to boulanger

either for better reproducing the /u/ phoneme of bulla (swelling

object, bubble), or for a more precise graphical representation of a quasi-hemispherical

object such as a loaf of bread and its mold. Yet, in French, bol primarily means clay, but

retains meanings of concave objects (e.g., anus), vessels (vein), and

containers (bowl, pot, jar, cup, earthenware), while its inverse, lob, is used for flat-convex objects such as lobe or the trajectory of a ball thrown to a significant

height.

Here is a

mechanism of semantic drift that may cause a blō-object (e.g., blōmos, bread)

to be interpreted as a bōl-object (e.g., boulanger,

baker), and vice versa, as announced above. The French phrase boule de glace

means a scoop of ice cream. Does the term boule refer to

the spherical mass of ice-crème artistically rounded by the scoop or to the

scoop itself, which is a hemispherical hollow tool? Very few do care in everyday

life! For some, perhaps for most of the people, boule erroneously

evokes the filled, convex, sphere of ice-crème they eat, which resembles a ball

(A for filling) or globe. For others, boule is the scoop resembling an

empty, hollow, concave bowl (/boul/), used for measuring the

amount of ice-cream to serve and, eventually, shaping it nicely. Similarly, in

the context of bread-making, the French and English boule bread (Fig. 13) probably refers to the bowl used for measuring

the amount of dough and for shaping the bread rather than to the shape of the

bread itself.

Figure 13. Boule bread. Artwork by Zantastik. Creative Commons license.

The French bluteau,

associated with Old French buretel, buletiel, blucteau,

buleteau, blutoir, and thought to

derive from the verb buleter or bluter + suffix -eau, is a

bread-making utensil today interpreted as sieve. No precise definitions exist for

those ancient terms. Their variable spelling is commonly attributed to brute dissimilation,

but it may also correspond to subtle, though significant semantic differences, e.g.,

evolutionary variants of the tool, different uses, or downright different tools. A graphocentric theory would explain, for example, buleteau as bule

+ eau, giving bule-t-eau, i.e., the mixture of dough (bule)

with water (French eau) – or a tool (e.g., container) for making such mixture

– with the archaic (“Phoenician”) grapheme + read as T. Instead, bluteau

would be blu + eau, i.e., the expansion, blow up, blow (blu,

of dough) by adding (+) water (eau); or the additional rising of the

dough written as blu + Ω (pronounced like French eau), and the container where it occurs. Similarly, blutoir

would be the place, surface, or container (typical meanings of the French

ending -toir) where the rising (blu-) occurs.

Regarding the second stem, -anger

of boulanger or -engarius from bolengarius, we

need not invent unattested languages and roots. In French, the E of -engarius

is nasalized as /ɛ̃/, which is very close to French cardinal /a/ (French /en/ ~= Latin /an/

and Greek /ang/ from agg-). Therefore, -engarius phonetically

matches the Latin angărĭus, from angărĭo, to demand something as angaria (Greek ἀγγαρία; aggaria;

/angaria/; service to a lord, villeinage), to exact villeinage, from Greek

ἀγγαρεύω (aggareyō; /angarevo/), to press into service, constrain,

press one to serve as an ἄγγαρος (aggaros; /angaros/; mounted courier, of mules, term of

abuse), probably akin to Assyrian agarru, hired laborer. In the

Byzantine lexicon of Hesychius, ἀγγαῤῥία (aggarria; /angaria/) follows the Assyrian spelling

with double-R and is explained as δουλεία (douleia), bondage, thrall, slavery, slave-class, hire service. The Egyptian root <Ar>, appearing in angărĭus,

is written with the Gardiner hieroglyphs T12 and A24, representing a bowstring

(for items that are hard, durable, strong), and a man striking with both hands

(to hit or strike, power, strength, teach a lesson or instruct),

respectively, and means to oppress (the poor). In Modern Greek, δουλεία (douleia;

bondage, slavery) differs from δουλειά (douleia; work, labor, task, employment, business, opus, deed,

doing, service) only in the tonic accent. Work may be felt as bondage when it

is not justly remunerated.

Following this etymological

analysis, the original and most accurate meaning of boulanger was not the

noble bread maker but a dough-boule maker, a serf hired for kneading: boule

+ angărĭus. Graphemes, phonemes, and sememes, circulate and recombine

anywhere in Egypt, Assyria, Persia, Canaan, Anatolia, Greece, Latium, and

Europe. Obsessive classification of languages using Indo-European, Turkic, and

Semitic family tree models may, indeed, be inappropriate, at least as far as

the vocabulary is concerned. We do not know if the ’Išbaʿal inscription BOL (Ϭ𐰧Ͻ; Fig 8, characters 3, 4, and

5) was an attempt to write the Late Egyptian term <bwl> in linear

European script or if the Late Egyptian had borrowed some Indo-European term

created by ichnography as B℧<.’ Išbaʿal is probably a Semitic

phonetic rendering of the same term for a kind of bowl, pottery material, or

method, not a proper name; and baʿal, or Baʿal, is not a deity

but a bowl.

In addition to ἄσβολος (asbolos;

soot, literally as-bolos = fire-clay), we find sbē (/sbiː/) in Homeric

ἔσβη (esbē;

aorist of σβέννυμι, sbennymi),

to quench, put out, extinguish (of fire),

dry out (of liquids); θίσβη (thisbē;

glossed by Hesychius as σορός), a vessel

for holding human remains, a cinerary urn; Modern Greek σβήνω (sbēnō),

to quench, switch off, turn off, burn out, extinguish; and in English asbestos. The etymology and literal meaning of the latter term

are presented as certain but may be inaccurate. Asbestos, referring to a

fireproof material, is paradoxically explained as inextinguishable (Plin. Nat. 19.4), from the privative prefix a-, not, and sbestos (σβεστός), verbal adjective

from sbennymi, to quench, from PIE root *(s)gwes- to quench, extinguish. To resolve the contradiction between fireproof and inextinguishable, it has

been proposed that asbestos fibers were used for making inconsumable wicks

There is a different solution to the asbestos

confusion. Another word, ἀμίαντος (amiantos) has been used in

Greek for the fireproof material. It is made of the privative prefix a-

and μιαντός (miantos; stained, defiled), from the verb μιαίνω

(miainō; to stain, sully, taint, defile; see section Cadmus and Cilix) and means

undefiled, pure, free from stain, not to be defiled. As an adjective of λίθος (lithos;

stone), amiantos lithos specifies asbestos. By analogy, asbestos

is always split as a-sbestos, thinking of a privative a- and the

verb sbennymi (to quench). Perhaps, this splitting is wrong.

With an archaic Asb meaning glowing

flame and ἕννυμι (‘ennymi)

meaning to put clothes on, cover, wrap, shroud, wear, Asb-‘ennymi

could have adapted to Greek grammar as sb-ennymi (sbennymi; to quench),

originally meaning to cover fire with cloths. Among various Homeric aorist

forms of ‘ennymi, we find ἕστο (‘esto, ϝesto, vesto or hesto; Il.23.67). It

compares to Latin vestis (the coverings for the body,

clothes, garments clothing, vesture, carpet, curtain, tapestry, any sort

of covering or coating), Sanskrit váste (clothes himself),

and Greek βεστίον (vestion)

and βέστον (= ἱμάτιον; veston),

both meaning clothing, a piece of dress, an outer garment, generally, clothes. The stem esto or besto (pronounced /vesto/) is found in

all, ἄσβεστος (asbestos) glossed as not quenched, also unslaked

lime (calcium oxide), plaster, ἀσβέστινον (asbestinon), non-combustible

material, Modern Greek ασβέστης (asbestēs), unslaked lime, quicklime

or burnt lime, ἀσβέστιον (asbestion), calcium, and English asbestos. Unslaked lime, quicklime, or burnt lime (Greek asbestos or asbestēs)

is produced by the thermal decomposition of materials, such as limestone or

seashells, that contain calcium carbonate, by heating the material in a lime

kiln to above 825 °C (1,517 °F)[3]. The burnt sememe

resides in the asb (or Egyptian <Asb>) stem of asbestos

and its cognates. Thus, asb-est-os reads as the fire-cloth, fire-cover,

or fire-coat thing.

Evidently, these stems form a basis with fire-protection semantics which may be ichnographically elaborated to modulate the meaning of derivative terms. Fire protection may mean protection of the fire or protection from the fire. A covered fire is protected from rain and strong winds which may extinguish it. A well covered and protected fire is relatively unquenchable (asbestos), but the Greek adjective asb-est-os literally means protected fire, not unquenchable (a-sbestos). The English asbestos reuses the stems to name a material that protects from fire, a fire-proof coat or cloth. The unslaked lime is a burned (asb) coating (est) thing (os), asb-est-os. Using the same term for a well-protected fire and a fired material will inevitably cause confusion. The Ancient Greek term asbestos for burnt lime evolved to Modern Greek asbestēs, where the confinement of a protected fire, evoked by a circle (O), was replaced with the sememe of a large surface evoked by H (ē). Firing renders some materials, such as clay (bol-os), fireproof. Fired earthenware resists cooking conditions, whereas raw clay vessels may break. A fired, fireproof clay vessel could well be called asb-bol, contracted as asbol (fired bowl). To extinguish a fire, we normally stop feeding it. The letter A is interpreted as filling throughout in this series of essays.

Similarly, in Asb, i.e., glowing, radiant (fire; Egyptian Asbyw),

A provides the sememe of filling in the sense of feeding the fire. By removing

the A from Asb, we essentially stop feeding the fire. We

thus finish with a sb-est, as in sbestos (σβεστός), meaning quenched,

extinguished, i.e., not fed.

The crosstalk between Egyptian and Greek also

provides an elegant secular interpretation of the rest of the ’Išbaʿal inscription …IBSIBDO. After the

invention of Greek Ψ (Psi; /ps/), the cluster IBS would be transliterated in

Greek as IΨ. The Homeric ἴψ (ips)

has been translated as a borer, a worm that eats wood and opens holes. Most

likely, the animal was named borer after its characteristic behavior of

entering a solid material and leaving a hole behind or blocking a hole (Table 1). A tool for opening holes could have been

named after ips, but ips may also create names for objects that fit

into holes, like a stopper or a cork (ἴψος;

ipsos) The inverse

stem, <bsi>, means flow forth of water in Middle Egyptian

It is possible that some of these roots

were somewhat misinterpreted by modern translators of either Egyptian or Greek. Alternatively, Egyptian writing was not as rigorous as Greek. For example, the

metathesis of I from <isb> to <sbi> has no semantic

consequences in Egyptian since both stems mean vanish. The Egyptian <bsi>

is comparable to Greek stem psi, both related to flow, but the inversion

ibs creates an antonym of flow only in Greek; <ibs> is

unrelated to flow in Egyptian. Instead, the Late Egyptian flow words, <bsi>

and <sib>, derive from Middle Egyptian <sbi>, drink, by

reshuffling metathesis of I or B. In Late Egyptian, <sib> has many

seemingly unrelated meanings, among which we find the morphologically similar

English terms flower, as well as jackal,

judge, joy, and javelin

– all starting with the extremely rare J – suggesting an iconic relation of J

with <sib>. A javelin is also semantically related to English flow

since, of solids, to flow means to undergo

a permanent change of shape under stress, without melting. As a javelin, <sib>

would describe the method of manufacturing such objects.

Greek uses sib, supplemented with -ύνη (-ynē), to form σιβύνη (sibynē) for objects similar to a javelin like a spear or a pike. The stem ynē is a concatenation of yn, from ὐνω (ynō; to make thin, pare away, fine down, grind small; or become thin, watery, of a fluid), with H (ē) for length. The antonymy produced by inverting SIB into BIS can be sensed in Fig. 14, comparing sibynē (spear, pike) to bis-derivatives like βίσβη (bisbē), a pruning hook, or βίσων (bisōn), bison. Mainstream phonocentric theory suggests that bison is ultimately of Baltic or Slavic origin (the existance of the Ancient Greek cognate remains unnoticed), and means the stinking animal in reference to its scent while rutting.

Figure 14. Objects named after the inverted Greek stems sib and bis. The sib-objects (from sibynē: A=spear, B=pike) are long, linear, sharp 'killing tools' (weapons). The bis-objects are short, curved, sharp 'killing tools' like the pruning hooks (bisbē; C and D) or the horns of a bison (E).

When supplemented with

the particle δή (dē; in truth, indeed, surely, really, quite, verily, like, so, this

and no other, above all, plainly, very, only) to provide further exactness, sib

gives σίβδη (sibdē), flow, flux. Metathesis of

Sigma from the beginning of sibdē to the end of ibdēs

(ἴβδης) creates an

antonym of flow (sibdē), the flow-stopper (ibdēs;

cock, plug). An object represented by Sigma seems to change position from

front to back to allow flow or stop it. Once more, semantics correlate with

morphology in Greek but not so in Egyptian. It may be proposed that Greek

borrowed Egyptian roots and organized them into an improved, systematic writing

system whereby graphemes and word morphology suggest a meaning. Alternatively, Late

Egyptian randomly borrowed Greek constructs ignoring the rules under which

these were created.

Finally, the cluster

BD (lips + passage) is combined with A (filling) to give BDA as in βδάλλω

(bdallō), to milk, suck, and with E (opening) for βδέω

(bdeō), to break wind. Thus, BDA is for in-flow and BDE

for out-flow through an orifice.

Table 1. Semantic analysis of IBSIBDO.

|

IBSIBDO |

EGYPTIAN |

GREEK |

|

|

IBS (IΨ) |

<ibs> headdress

(Middle Egyptian) <ibi> be thirsty

(Middle Egyptian) |

ιψ (ips) ἴψος (ipsos) |

wood-worm borer cork |

|

BSI (ΨI) |

<bsi> flow, flow

forth (of water), influx, introduce, induct, emerge, admit into, initiate, install |

ψῖ (psi) ψίω (psiō)

ψιάς (psias) |

letter Ψ feed on pap, give to drink drop |

|

ISB |

|

|

|

|

SBI |

<sbi> drink (Middle

Egyptian), go, travel, attain, watch over, send, conduct, spend, pass,

attain, approach, be faint, perish, vanish <ssbi> despatch (deprive?) |

|

|

|

SIB |

<sib> flow, jackal,

dignitary, judge, speckled snakes, destroy, flower, joy, javelin, sloth |

σιβύνη (sibynē) |

spear, pike |

|

SIBD |

<Sibd> stock |

σίβδη (sibdē) |

flow, flux |

|

SIBDO |

|

στιβδός (sibdos) |

pricked, tattooed, dappled |

|

IBD |

<Ibd> month |

ἴβδης (ibdēs) |

cock or plug in a ship’s bottom |

|

IBDO |

<Ibdw> fish |

|

|

|

BD |

natron, glaze |

βδάλλω

(bdallō) βδέω

(bdeō) |

to milk, suck to break wind |

Claims

The frequencies of letters, or letter clusters, may establish graphocentric linguistic phylogenies or identify a language behind an undeciphered script.

The Ishbaal inscription may be read as Greek, meaning ashtray (ash-bin, dustbin), soot-ink decorated, or fired bowl with bottom-flow control [tap].

Cognates

Ishbaal (Greek root AShBOL-): English ash.

BOL: English bowl.

References

Ager, S., & Paliga, S. (2021). Vinča symbols. Omniglot.

Alleman, J. E., & Mossman, B. T. (1997). Asbestos Revisited. Scientific American, 277(1), 70–75.

Augustyn, A. (2020). Philistine. In The Editors of Encyclopaedia (Ed.), Encyclopedia Britannica. britannica.com.

Beekes, R. S. P. (2014). Pre-Greek: phonology, morphology, lexicon. Brill.

Beekes, R. S. P., & Beek, L. van. (2010). Etymological dictionary of Greek. Brill.

Benz, F. (1972). Personal names in the Phoenician and Punic inscriptions : a catalog, grammatical study, and glossary of elements. Biblical Institute Press.

Coleman, J. E. (2000). An Archaeological Scenario for the “Coming of the Greeks” ca. 3200 B.C. The Journal of Indo-European Studies, 28(1–2), 101–153.

Daniels, P. T., & Bright, W. (1996). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press.

Dickson, P. (2006). Dictionary of Middle Egyptian. Open source.

Drinka, B. (2013). Phylogenetic and areal models of Indo-European relatedness: The role of contact in reconstruction. Journal of Language Contact, 6(2), 379–410.

Dunand, M. (1978). Nouvelles inscriptions pseudo-hiéroglyphiques découvertes à Byblos. Bulletin Du Musée de Beyrouth, 30, 51–59.

François, A. (2015). Trees, waves and linkages: Models of language diversification. In C. Bowern & B. Evans (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics (pp. 161–189).

Gimbutas, M. (1986). Remarks on the ethnogenesis of the Indo-Europeans in Europe. In W. Bernhard & A. Kandler-Palsson (Eds.), Ethnogenese europäischer Völker (pp. 5–19). Gustav Fische Verlag.

Gimbutas, M. (1997). The Kurgan culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected articles from 1952 to 1993 (Vol. 18). Institute for the Study of Man.

Naveh, J. (1978). Some Considerations on the ostracon from ʿIzbet Ṣarṭah. Israel Exploration Journal, 28, 31–35.

Renfrew, C. (1973). Problems in the general correlation of archaeological and linguistic strata in prehistoric Greece: the model of autochthonous origin. In R. A. Crossland & A. Birchall (Eds.), Bronze Age migrations in the Aegean; Archaeological and Linguistic Problems in Greek Prehistory: Proceedings of the First International Colloquium on Aegean Prehistory, Sheffield (pp. 263–276). Duckworth.

Sass, B. (2019). The Pseudo-Hieroglyphic Inscriptions from Byblos, Their Elusive Dating, and Their Affinities with the Early Phoenician Inscriptions. In Par la bêche et le stylet! Cultures et sociétés syro-mésopotamiennes (pp. 157–180). Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

Sass, Benjamin. (1988). The genesis of the alphabet and its development in the second millennium BC. Harrassowitz.

[1] Amarna

letters in English Wikipedia. Accessed 23 August 2021.

[2] Byblos

Necropolis graffito in English Wikipedia; accessed 30 June 2021.

[1] In the American Heritage Dictionary, the only Semitic word ending in -yw, is <ḥyw>, to live. Instead, there are many Ancient Egyptian words ending in -yw. With very few exceptions, they describe or refer to people, i.e., objects that rise and fall, live and die. From Dickson (2006) we gather: <aDyw>, winnowers; <aHwtyw>, cultivators; <antyw>, myrrh; <artyw>, they who ascend; <Asbyw>, flames; <Axtyw>, horizon - dwellers (a remote people; <bAgyw>, the languid ones (the dead); <bnrytyw>, confectioners; <bSttyw>, rebels; <bwytyw>, those who are abominated; <DAytyw>, opponents; <DAyw>, opponent; <Drtyw>, ancestors; <dwAtyw>, dwellers in the netherworld; <HAyw>, carrion - birds; <Hmsyw>, guests; <Hmwtyw>, craftsmen; <Hnsktyw>, wearers of the side-lock (of hair); <Htptyw>, the peaceful ones (the blessed dead); <Htpyw>, non-combatants; <iAbtyw>, Easterners; <iAtyw>, mutilation; <imAxyw>, revered ones (of the aged living); <imntyw>, Westerners; <iryw>, crew (of boat); <iwntyw>, tribesmen; <iwtyw>, corruption; <kftyw>, (locality) Crete ?; <knmtyw>, they who dwell in darkness (name of a conquered people); <mAatyw>, just men, the righteous (the blessed dead); <mabAyw>, the Thirty (a judicial body); <mHtyw>, northerners; <msTyw>, offspring; <myw>, semen, seed of man; <nDtyw>, maidservants ?; <niwtyw>, citizens, townsmen; <nnyw>, inert ones (the Dead); <nsyw>, Kings; <pAwtyw>, men of ancient families; <pDtyw>, foreigners; <pwntyw>, the people of Punt; <r pDtyw>, foreigners; <rmnwtyw>, (pl.) companions; <rsyw>, Southerners; <sDAwtyw>, treasurers; <sdtyw>, weaklings; <smntyw>, emissaries; <smytyw>, owners of a desert tomb; <spAtyw>, nome-men; <sTtyw>, Asiatic; <styw>, Asiatic, Nubians; <sxryw>, those who govern; <wHAtyw>, oasis - dwellers; <xAstyw>, foreigners, desert-dwellers; <xbstyw>, bearded ones; <Xnwtyw>, skin - clad people; <xrwyw>, war.

[2] See also boulanger in Wiktionary. Accessed 16 June 2022.

[3] Calcium oxide in English Wikipedia; accessed 19 June 2022.

.jpg)